Saturday, July 24, 2010

Monday, July 12, 2010

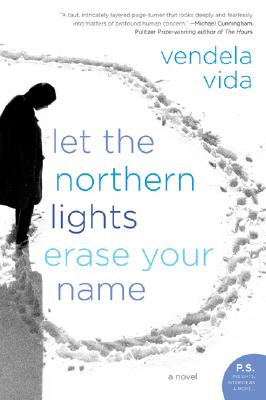

Vendela Vida's LET THE NORTHERN LIGHTS ERASE YOUR NAME

A waterfall of effusive praise spills across the first four pages of my paperback edition of Vendela Vida's novel, Let the Northern Lights Erase Your Name. Compelling. Economical. Lush. Spare. Unflinching. Precise. Searing. It is a somewhat confusing thesaurus (how can something be both economical and lush? Perhaps this is a failure of my own imagination) and for some reason it left me skeptical. It was as if all the praise roused my inner contrarian and I wasn't on the book's side at the beginning. Ultimately, I liked it. I didn't love it, but there is so much to admire in Vida's skill as a prosodist that it balanced out the elements of the story that strained my credulity.

SPOILER: Here's the basic plot outline, minus the climactic finale: Clarissa's mother abandoned her when Clarissa was 14. Clarissa is now in her late twenties. After her father dies she finds out that he wasn't her biological father. Then she finds out that her fiance knew about that and didn't tell her. So she goes to Finnish Lapland to find her biological father (without telling anyone back home). Turns out the person named on her birth certificate as her father isn't her father either. Turns out her mother was raped and the rapist is Clarissa's father. Turns out Clarissa, too, was raped (when she was a teenager). Clarissa discovers she is pregnant with her fiance's child. Incredibly, Clarissa finds her long-lost mother in Lapland. Her mother ignores her and, when forced to acknowledge her, reinforces what she made clear when she left in the first place: she doesn't want to be a mom. And on and on the story goes, in a tight spiral that reiterates its favorite theme after every revolution: Major Communication Breakdowns Hurt and Define Clarissa.

While I did find the plot a bit too taut (everyone, from the shuttle bus driver in Helsinki to the dudes Clarissa meets in the mini mart have a pointedly meaningful role to play) and melodramatic, and the evocation of Finnish Lapland was patchy, Vida's prose is mesmerizing. In Clarissa Vida has created a voice that is direct, unwavering, and brazen. I read the book in two great gulps over the period of two days, and part of the reason I couldn't put it down was because Clarissa felt like that girl in sixth grade with black fingernail polish who talked back to teachers and dared me to go up to boys I didn't know and ask for their phone numbers. Clarissa must navigate an unthinkable situation. She takes powerful, direct action, action with high-stakes consequences. She strides through the novel with a force that is daunting and delicious.

The other reason I didn't want to put down the book was the charm of Vida's similes. Here's my favorite: Recently, everything around me felt familiar yet amiss, like the first time you ride in the back seat of your own car. It is a simple, perfect simile. It illustrates exactly why writers should continue to employ them. It points straight to something unmistakable. After I read it I was almost embarrassed by the intimacy I suddenly felt with the author, because I know exactly the feeling she references. So did my boyfriend when I read the sentence aloud to him - he smiled and nodded, and so too would any car owner who has found himself in that weird backseat position. The novel is littered with such jewels. Collecting them is the novel's primary pleasure. In the end, it is a pleasure well worth the read.

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Craft

I've always been uncomfortable calling myself an artist. As a novelist, I understand my "art" not so much as the numinous kernel at the heart of every painting, sculpture, poem, and novel, but as the perseverance, the doggedness it takes to build a form for that kernel to live in. For me the word art implies magic, and while I am the first one to admit that there is something inexplicable and nourishing (not to mention gratifying) about those moments when something unexpected and spontaneously right spills onto the page and becomes a touchstone leading me forward, most of the time I am working on my craft in a decidedly un-magical way. I am a craftsperson.

That said, sometimes the word craft is unsatisfying. There is that pesky division we've created between high art and lower craft. Craft smells faintly of stencils and crocheted stuffed animals. Or, it can imply purely utilitarian objects. Often, when I put down my "real work" of the day and amble out to the workshop to spin fiber, knit, or dream up a sewing project, I feel just a tiny bit frustrated to be moving "down" to handiwork, and that downward movement implies a departure from the world of ideas into something not quite as valuable. For years I've demoted all the crafts I practice. In this way of understanding things, I've denied the myriad ways that craft integrates and transforms my consciousness.

That said, sometimes the word craft is unsatisfying. There is that pesky division we've created between high art and lower craft. Craft smells faintly of stencils and crocheted stuffed animals. Or, it can imply purely utilitarian objects. Often, when I put down my "real work" of the day and amble out to the workshop to spin fiber, knit, or dream up a sewing project, I feel just a tiny bit frustrated to be moving "down" to handiwork, and that downward movement implies a departure from the world of ideas into something not quite as valuable. For years I've demoted all the crafts I practice. In this way of understanding things, I've denied the myriad ways that craft integrates and transforms my consciousness.A Way of Working: The Spiritual Dimension of Craft is a book edited by D. M. Dooling (1910-1991), the founder of Parabola magazine. So far I've only read three of the essays in this slim volume, but already they've lent a crucial hand in reconciling my mistake in splitting art from craft. I sense a profound consequence for me personally in mending this rift. To be able to see my work as knitter, spinner, and designer as kindred in some way to my work as a novelist, and not "lower," is a great step toward inner unity, one that I am eager to take. From the introduction to A Way of Working:

"Craft" originally meant "strength, skill, device," indicating at its very inception the basic relationship of the material, the maker, and the tool: the opposition of thrust and resistance and the means of their coming together in a creative reconciliation. The artist must be a craftsman, for without the working knowledge of this triple relationship subject to opposing forces, he has not the skill to express his vision. And if the craftsman has no contact with the "Idea," which is the vision of the artist, he is at best a competent manufacturer. Art and craft are aspects (potential, not guaranteed) of all work that is undertaken intentionally and voluntarily...Both art and craft must take part in any activity which has the power to transform.

Friday, June 18, 2010

An Important Message from Unknown Inuit Elder

My imagination is spiraling northward toward the arctic. Ever since I encountered the landscape of the far north for the first time in the summer of 2004, I have been thinking about it, first through the prism of my experience there, and then through the lens of my craft, fiction. Regarding the fiction aspect, at first I was horrified. My feeling as I hiked across the tundra, among the cotton grass and moss campion cushions, among razorwinged jaegers, gyrfalcons, and rock ptarmigan, as I glimpsed cross foxes and grizzlies, as I walked breathless in the slanted light of a summer solstice midnight, I realized this: fiction is completely irrelevant to this place. When you have watched a wolf amble across the tundra and swim across a braid of the Canning river to raid a gull's nest, when you have observed this creature free in its natural domain...and when you have lain in your tent and feared, on some level, for your life, and wondered if it was possible for a post-millenial urban human being to end up grizzly prey (and felt a certain rightness about human as prey

), artifice falls away, at least it did for me. Experiential knowledge trumped art in every significant way. The far north is wild, magnificent, sublime. To describe it, I thought, does it an injustice, because how could I not taint and temper its power by my own weakness (as a writer, as a vessel of human perception). The truth is, being in the arctic just about re-calibrated the artist right out of me.

), artifice falls away, at least it did for me. Experiential knowledge trumped art in every significant way. The far north is wild, magnificent, sublime. To describe it, I thought, does it an injustice, because how could I not taint and temper its power by my own weakness (as a writer, as a vessel of human perception). The truth is, being in the arctic just about re-calibrated the artist right out of me.After a while, I began to think about it differently. An old adage ran through my head: When the student is ready, the teacher appears. Just before I went to the Alaskan arctic I had graduated with an MFA in fiction. When I returned from that hiking and rafting trip north of the Brooks range, I wondered if my schooling had been in vain. I felt like 12 days in the arctic showed me more about the creative process than those two years in school.

Luckily I've changed my view somewhat. One day I was complaining about all this to my boyfriend, and he said: "So don't describe it. Create it." And somewhere in those two short sentences I dug in my heels and grabbed hold of the thread of an idea, the end of a guide rope, let's say, and began to follow the spiraling path into my next book.

When I beg

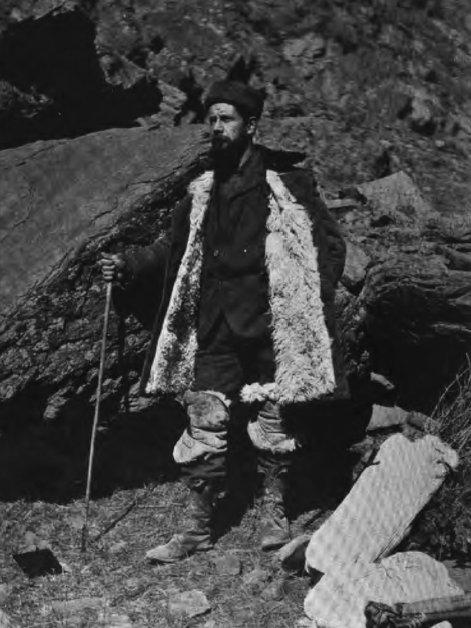

an to research arctic narratives, I encountered expedition after expedition, and while accounts of egomaniacal captains and very bad 19th century planning intrigue me no end, and I love the macabre dynamics among the men on those ships, I leaned away from the expeditionary tales. What I'm leaning toward is still mysterious, but it is unfolding itself over time: the Russian Orthodox ascetics of the north, the tales of the Pomor hunters, Salomon Andree's journals, and most of all Spitsbergen, the great archipelago that no country claimed until almost the 20th century. This place, this icy terra nullis, has become the most fertile and bountiful imaginative landscape to me.

an to research arctic narratives, I encountered expedition after expedition, and while accounts of egomaniacal captains and very bad 19th century planning intrigue me no end, and I love the macabre dynamics among the men on those ships, I leaned away from the expeditionary tales. What I'm leaning toward is still mysterious, but it is unfolding itself over time: the Russian Orthodox ascetics of the north, the tales of the Pomor hunters, Salomon Andree's journals, and most of all Spitsbergen, the great archipelago that no country claimed until almost the 20th century. This place, this icy terra nullis, has become the most fertile and bountiful imaginative landscape to me.

A few weeks ago I was reading an essay and found a quote that speaks directly of the arctic and the creative process. Typical of arctic narrative, there are many layers to the quote's authorship. It appears in a book called Echoing Silence: Essays on Arctic Narrative, in an essay by Aron Senkpiel. In the essay Senkpiel quotes Knud Rasmussen, the Greenlandic polar explorer and anthropologist, who in turn quotes an unknown Inuit elder from Pelly Bay, in Canada's Nunavut territory. This person, this unknown elder, is speaking of the creative process, and for me this quote is incredibly useful and inspiring as I take one slow step after another northward, to write about the arctic.

A perso

n is moved just like the ice floe sailing here and there out in the current. Your thoughts are driven by a flowing force when you feel joy, when you feel fear, when you feel sorrow. Thoughts can wash over you like a flood, making your breath come in gasps and your heart pound. Something like an abatement in the weather will keep you thawed up. And then it will happen that we, who always think we are small, will feel even smaller. And we will fear to use words. But it will happen that the words we need will come of themselves. When the words we want shoot up of themselves-then we get a new song."

n is moved just like the ice floe sailing here and there out in the current. Your thoughts are driven by a flowing force when you feel joy, when you feel fear, when you feel sorrow. Thoughts can wash over you like a flood, making your breath come in gasps and your heart pound. Something like an abatement in the weather will keep you thawed up. And then it will happen that we, who always think we are small, will feel even smaller. And we will fear to use words. But it will happen that the words we need will come of themselves. When the words we want shoot up of themselves-then we get a new song."Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Thanks again, Frans Meijer

In our age of declining biodiversity, it's difficult to imagine a time when the US Department of Agriculture regularly hired explorers to hunt down new fruit and vegetable varieties across the globe. But this is exactly what Frans Nicholaas Meijer was hired to do in 1905. During his stint as a USDA agricultural explorer, he traveled all over the world and returned with many new species that went on to be widely cultivated in the States. He is best known for his Chinese imports, including Gingko biloba, soybeans, and Chinese cabbage, among others. Apparently afflicted with a severe case of wanderlust, he spent his adult life traveling, sometimes on foot across vast distances. Sadly, in 1918 at the age of forty-three, he drowned in the Yangtze river.

I am particularly grateful to Meijer for bringing us the lemon that now bears the anglicized version of his name. Thought to be a cross between a lemon and a mandarin, the round, thin-skinned Meyer lemon has a delectable floral scent and taste, and is less bitter than a Eureka or a Lisbon. There are two abundant Meyer lemon trees in our yard, and this yellow jewel has provided us gallons of lemonade, (often infused with rosemary), quarts of marmalade (honeyed and vanilla bean), limoncello galore, and Moroccan style preserved lemons, not to mention untold squeezes over salads, poultry and fish. But there is one recipe that stands above all the other lemon-oriented delicacies I’ve made, a recipe so heavenly, so wickedly and perfectly decadent that the people who eat it swoon off their chairs. It is something I would have loved to make for Frans Meijer in gratitude. My landlord, the man who planted the trees in our yard, handed me the recipe very casually a few months ago. Let's just say my response upon first tasting the result was anything but casual. I would describe it more as a joyful seizure. It is Meyer Lemon Custard Cream Pie. Yeah. It is insanely good. This recipe is from Sunset Magazine. There’s no date on the photocopy my landlord gave me, but the short article is by Elaine Johnson.

Meyer Lemon Custard Cream Pie

Prep and cook time: About 40 minutes, plus two hours for chilling.

Makes one pie.

10 (about 2/13 lb.) Meyer lemons

1/3 cup cornstarch

1 cup sugar

3 large eggs

1 baked, cooled 9-inch pastry shell, or one homemade baked, cooled pie crust

1. Grate 2 teaspoons peel from lemons. With a zester or Asian shredder make a few long strands of peel to decorate the finished pie. Squeeze one and one-third cups juice from the lemons.

2. In the top of a double boiler (I use a makeshift boiler using two saucepans and it works fine), mix the cornstarch and sugar. Stir in the lemon juice and grated peel. Fill the bottom of the double boiler with 1 inch of water. Place pans over high heat and bring water to a simmer. Stir until the mixture isthick and shiny, 8-9 minutes. In a bowl, whisk eggs to blend. Whisk in about ½ cup of lemon mixture, then return all to pan. Stir until mixture is very thick and reaches 160 degrees on a candy thermometer, about 5 minutes.

3. Remove top pan. Place it in a bowl of ice and stir often until the mixture is cool to touch, about 6 minutes.

4. In a bowl, beat the cream with a mixer (or with a whisk, if you’re me) until stiff. Fold in lemon mixture, then spread evenly in pastry shell. Scatter reserved strands of peel on top and chill for a couple of hours. I’ve used rosemary blossoms, raspberries, and blueberries on top of the pie.

Thanks again, Frans Meijer!